Using behavioural science to promote better adherence to rehab or post-treatment advice

)

Behavioural Science

Behavioural science is the systematic study of human behaviour. The tenets of behavioural science could offer great value to your professional practice given the challenges you may experience in your day-to-day roles. For example, you might be challenged by poor client adherence to their rehabilitation programme. An understanding of the antecedents of human behaviour could help you to provide a service which is targeted and tailored to your client’s needs, and in turn enhance your clients’ health, wellbeing, and performance.

Adopting a Behaviourally Informed Approach

The important first steps in utilising behavioural science in practice are:

-

Identify the target behaviour(s) that you want to enable (e.g., the client performs rehab exercises twice a day).

-

Undertake a behavioural analysis to understand the barriers and enablers to the target behaviour(s).

Identifying What Needs to Change

A behavioural analysis is when practitioners take time to understand clients’ thoughts, feelings and experiences of doing the target behaviour(s) and identify the barriers that need to be targeted through a behavioural intervention to increase the likelihood that the target behaviour(s) will be performed consistently over time, as advised.

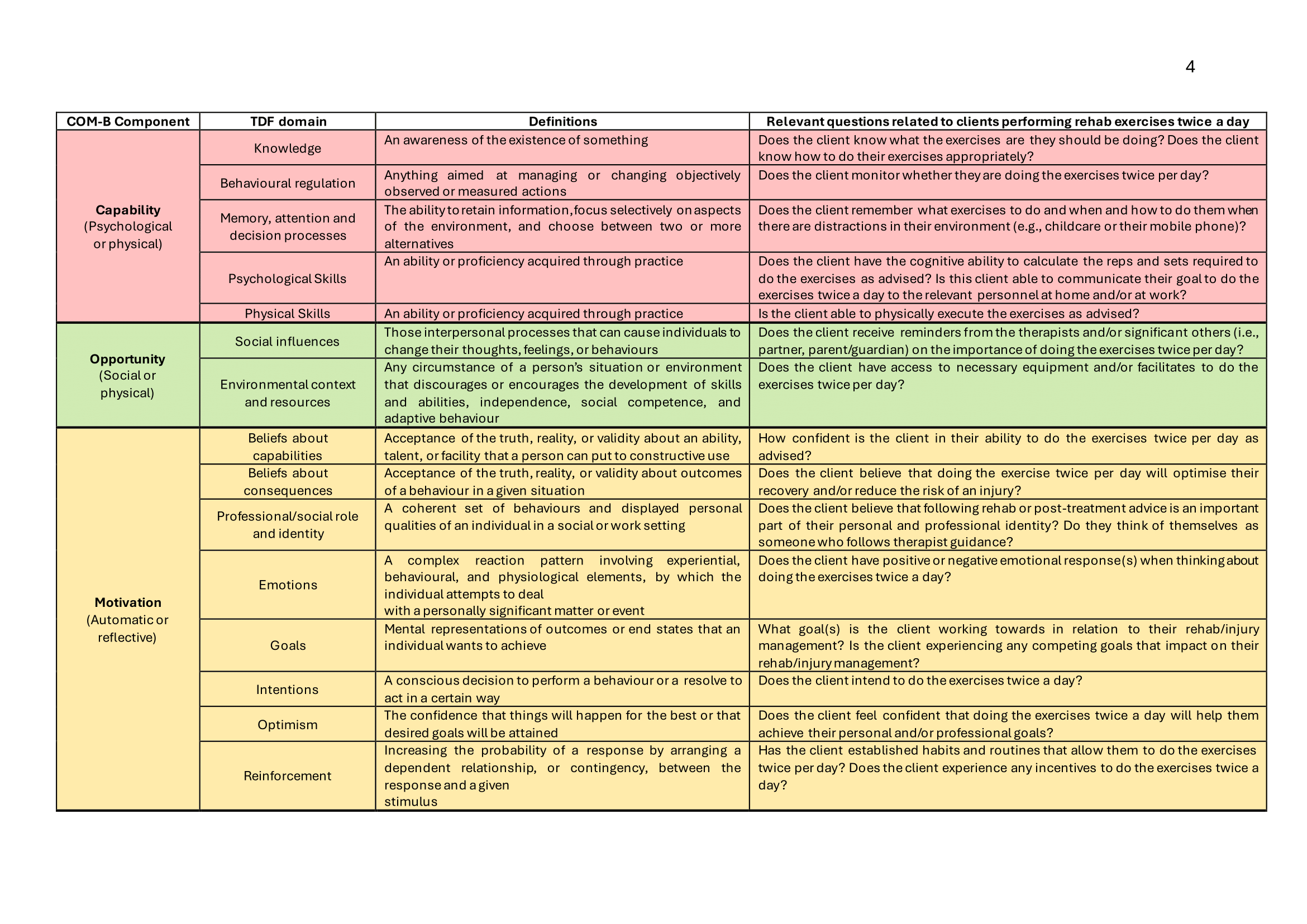

If we take the target behaviour “client performs rehab exercises twice a day”, the capability, opportunity, and motivation behaviour ( COM-B) model [1] recognises that for a client to enact this behaviour they must have:

-

The capability to do the exercises twice a day (e.g., knowledge of what the exercises are and how to do them, the physical skill to execute the exercises as advised, and the memory and attention to decide to do the exercises when presented with two or more alternative options).

-

The opportunity to do the exercises twice a day. Including the social opportunity (e.g., support from others) and the physical opportunity (i.e., the necessary equipment and/or facilitates).

-

The motivation to do the exercises over other competing behaviours that day. Motivation is the brain process that directs our behaviour and can be reflective (e.g., the client is confident that doing the exercises twice a day will help them achieve their personal and/or professional goals, and they are confident in their ability to do the exercises twice per day as advised), and automatic (e.g., the client has a positive emotional response when thinking about doing the exercises twice a day)

All three component are essential for behaviour to occur. Figure 1 is a schematic representation of the COM-B with illustrations of potential barriers to performing rehab exercises twice per day.

Figure 1: Capability, Opportunity, Motivation-Behaviour Model (COM-B) with client performing rehab exercises, twice a day, as the target behaviour. Adapted with permission from Michie et al., [1].

Each of the COM-B components map across to another behavioural theory, the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) [2], which together provide a synthesis of 33 theories of behaviour and behaviour change clustered into 15 domains [2]. The COM-B model and TDF provide a comprehensive framework for conducting a behaviour analysis. This overarching framework has been used to examine athlete adherence to nutritional guidance [3, 4], explore asthma medication use amongst competitive athletes [5], enhance oral health behaviours in elite athletes [6] and reduce the risk of inadvertent doping through supplement use [7].

Table 1 provides an overview and definition of each domain from the COM-B model and TDF, with example questions related to the target behaviour of the client performs rehab exercises twice a day. You are encouraged to reflect upon each domain to identify what needs to change to enable your client to perform the target behaviour(s) (adapted from Michie, et al., [7], Cane et al., [2], and Backhouse., [8], with permission).

Identifying and Implementing Behaviour Change Techniques

Once a behavioural analysis has been conducted the therapist will have a comprehensive understanding of the client’s rehab behaviour(s). Consequently, the therapist can identify the specific support needs of their client to enable them to perform the target behaviour. For example, perhaps the therapist has identified that the client has no established habits and routines that allows them to do the exercises twice per day (i.e., lack of reinforcements) or the client is unable to recall or is not monitoring when they are doing the exercises as advised (i.e., limited behavioural regulation). Once these barriers have been identified the therapist is able to select the activities that can be delivered to bring about change in the identified barriers, and in turn, enable the client to perform the target behaviour.

The next step in behavioural science is to select appropriate Behaviour Change Techniques (BCTs) that can be used to bring about change in the identified barriers. BCTs are the active components of a behavioural intervention that have the potential to make change happen [9]. They can be used alone or in combination with other BCTs, however research has identified links between BCTs and each domain of the TDF. Meaning that some BCTs are more effective at changing a domain of the TDF compared to others [10-12]. For example, if you identify a lack of reinforcement, you could use the BCT “Prompts & cues” whereby together with the client you help to define an environmental or social stimulus with the purpose of prompting or cueing the target behaviour (i.e., it is agreed that the client will do their exercises after they have brushed their teeth in the morning and in the evening). To address a lack of behavioural regulation, you might encourage “self-monitoring” whereby together with the client you identify a method for the client to record their behaviour (i.e., it is agreed that the client will complete a worksheet/or write a note using their mobile phone when they have done the exercises as advised).

If you would like to see a summary of the BCTs that can be used to target each domain of the TDF, you can explore the Theory and Technique Tool at

https://theoryandtechniquetool.humanbehaviourchange.org/tool

Another useful source of information is the Behaviour Change Techniques App, which is free to download and provides an overview and definitions of each BCT, with examples related to healthcare practice.

App Store:

https://apps.apple.com/us/app/bct-taxonomy/id871193535

Google Play:

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.BCTTaxonomy&hl=en_GB

Summary

The purpose of this article was to illustrate the potential value of behavioural science in advancing the professional practice of therapists. In particular, this article highlights the importance of obtaining an accurate understanding of the target behaviour in order to increase the likelihood of behaviour change. The COM-B model and TDF are useful tools to conduct a comprehensive behavioural analysis which subsequently informs the systematic selection of appropriate BCTs. Furthermore, the Theory and Technique Tool can help therapists identify the types of BCTs that they are already applying within their practice as well as identifying alternative approaches which have not yet been considered. As a result, behavioural science provides a process to inform the development of therapy service provision, seeking to enhance adherence to rehabilitation programmes, and in turn, optimise client health, wellbeing, and performance.

References

1. Michie, S., et al., The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 2011. 6(42): p. 1-11.

2. Cane, J., D. O’Connor, and S. Michie, Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implementation Science, 2012. 7(37): p. 1-17.

3. Bentley, M.R., et al., Athlete perspectives on the enablers and barriers to nutritional adherence in high-performance sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 2021. 52: p. 101831.

4. Bentley, M.R., et al., Sports nutritionists’ perspectives on enablers and barriers to nutritional adherence in high performance sport: A qualitative analysis informed by the COM-B model and theoretical domains framework. Journal of sports sciences, 2019: p. 1-11.

5. Allen, H., et al., Asthma medication in athletes: a qualitative investigation of adherence, avoidance and misuse in competitive sport. Journal of asthma, 2022. 59(4): p. 811-822.

6. Gallagher, J., P. Ashley, and I. Needleman, Implementation of a behavioural change intervention to enhance oral health behaviours in elite athletes: a feasibility study. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 2020. 6(1): p. e000759.

7. Michie, S., L. Atkins, and R. West, The behaviour change wheel: a guide to designing interventions. 2014, Great Britain: Silverback.

8. Backhouse, S.H., A behaviourally informed approach to reducing the risk of inadvertent anti-doping rule violations from supplement use. Sports medicine, 2023. 53(Suppl 1): p. 67-84.

9. Michie, S., et al., The Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy (v1) of 93 Hierarchically Clustered Techniques: Building an International Consensus for the Reporting of Behavior Change Interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 2013. 46(1): p. 81-95.

10. Carey, R.N., et al., Behavior change techniques and their mechanisms of action: a synthesis of links described in published intervention literature. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 2019. 53(8): p. 693-707.

11. Connell, L.E., et al., Links between behavior change techniques and mechanisms of action: an expert consensus study. Annals of behavioral medicine, 2019. 53(8): p. 708-720.

12. Johnston, M., et al., Development of an online tool for linking behavior change techniques and mechanisms of action based on triangulation of findings from literature synthesis and expert consensus. Translational behavioral medicine, 2021. 11(5): p. 1049-1065.

This article was submitted by Dr Meghan Bentley of Leeds Beckett University

If you would like to submit any new research pieces to feature in our monthly newsletter, please contact m.benson@closerstillmedia for more information.

.png)

.png)

.png)